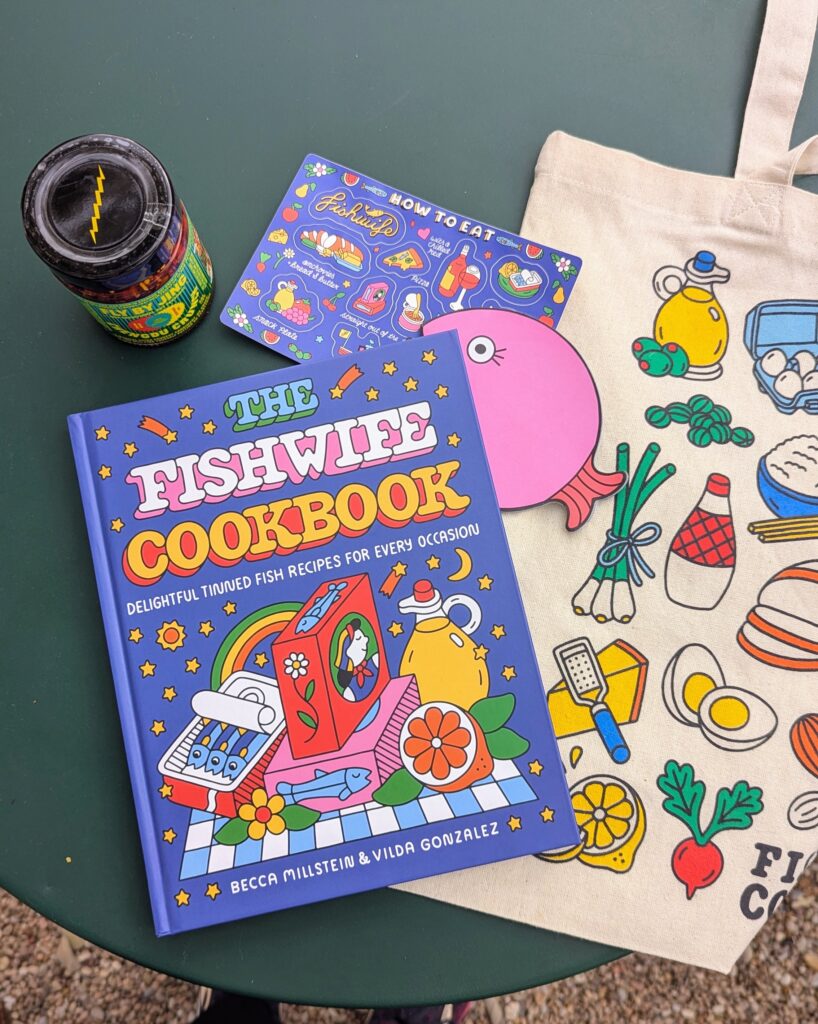

This weekend, First Light bookstore hosted a release party for the new Fishwife cookbook. Steph Steele of neighboring Tiny Grocer interviewed Fishwife founder Becca Millstein and Fly By Jing founder Jing Gao. Guests who RSVPed and bought a cookbook were also treated to snacks made with their products and delicious NA cocktails. I have never seen the inside of First Light so packed, although trivia night is so popular that quizzers will be sitting on the ground outside. Getting food required a litany of “I’m sorry!”s and even throwing away your trash meant elbowing perfectly innocent cafe customers waiting in line for wine. I’ve never been to a cookbook event at the bookstore before so I don’t know if they are all like this or if this one was particularly large because of SXSW. I showed up two minutes before the start time and I felt like I was the last to arrive. Luckily, I was still able to grab one of the swag bags available to early RSVPs.

The snacks were a panzanella and two different onigiri stuffed with Fishwife salmon or trout. The salad was my favorite though and I was eating it with my fingers. Fishwife is all about paying a premium for amazing illustrations that convince you that you want to eat tinned fish. Before Fishwife, I had grown up eating canned tuna but otherwise associated canned fish with Heathcliff and the Catillac Cats eating out of cans at the city dump. Eating this classy panzanella out of a fish can combined the two worlds of gourmet products and feeling like a cat having a snack on the street. The NA martini was sweeter than a normal martini and I hope that they add it to their normal cafe menu.

The founders discussed their origins, cultural connections, and challenges. I learned a lot about the logistics of packaging and shipping a small product! The entire audience gasped when Gao mentioned glass jars being shipped out in manila envelopes, but then she added, “wait, that’s not even the horror story I wanted to tell you about.” While Fishwife had to overcome the American aversion to tinned fish, Gao had to grapple with the “low-key and high-key racism” that Chinese food faces in the market. She was asked, “how can Chinese food be premium?” I am glad that they both persevered because the variety and quality of foods we have access to in our homes now is the best part of the 21st century.