Vegan cuisine lacks tradition.

There are examples of veganism or extreme vegetarianism going back to as far as ancient Greece and India, but most cases represent isolated individuals, not a lineage. There are few rare examples of near vegan cuisine being culturally sustained–Shojin Ryori and multiple Indian foodways for instance–but those are exceptions in the gastronomic world. Instead, veganism is more often associated with eschewing what came before, a deliberate turning away from a culture that shares different values.

As a result, most vegan cookbooks are instructional. The average reader is statistically probably unfamiliar with vegan cookery and in fact may have never had to prepare their own meals before, coming from a culture where meat-laden dishes can be delivered or picked up from a drive-thru. It is risky for a vegan cookbook to dive deeply rather than pan broadly, to presume even basic kitchen skills. This means we are treated less often to rich and uncompromising works like the beautiful and omnivorous Burma: Rivers of Flavor or Gran Cocina Latina.

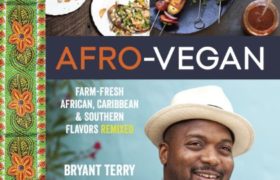

Bryant Terry has always resisted these trends in modern veganism, seeking to ground his food in history, even an omnivorous history. Starting with Vegan Soul Kitchen, he has linked his recipes to family stories, century old traditions, and modern cinema and music. In his latest work, Afro-Vegan he goes further than ever. He maintains the habit of suggesting other cultural works like songs to tie into each recipe, and of “remixing” classic recipes with new twists, such as combining Southern skillet cornbread with North African dukkah. Unlike his past books, however, he goes further in emphasizing the linkages between what he cooks, traditional African American foodways, and the cuisines of Africa.

The book organization shows his emphasis on African and New World ingredients. “Okra, Black-eyed Peas, and Watermelon” get lumped together in one chapter, while “Grits, Grains, and Couscous” share another. Every recipe showcases some element of African cuisine but no recipe seems explicitly foreign. Terry reworks every ingredient or technique until it fits our modern expectations. Okra is grilled to make a spicy finger food, African black eyed pea fritters appear in a more traditional form and as softer patties for sliders. A whole chapter is devoted to cocktails, demonstrating that this is not intended to be a manual to recreate some kind of authentic African experience, but rather to incorporate tiny bits of tradition into modern life.

Terry does not talk down to his audience or spend much time explaining what’s needed in a pantry or how to deep fry. Because of this, he doesn’t need to water down his vision. Every dish works in concert, delivering a pitch perfect demonstration of Terry’s style. Sometimes this requires uncompromising instructions. Making Slow-braised Mustard Greens–which I would usually toss into one pot and call it a day–requires one pot and two pans, but the result is the creamiest mustard greens I’ve ever had. Za’atar Roasted Red Potatoes included more steps than I would expect from roasted potatoes–including taking the potatoes out halfway through to re-season, then laying each piece back on the baking sheet “cut side up”–but my boyfriend declared them, “the best anything. Ever.” The specifications may seem particular, but in each case Terry reassures that this is worth it. When describing how to meticulously remove the skin from every black-eyed pea used in Crunchy Bean and Okra Fritters, he suggests inviting guests to help. Even in the preparation, he manages to work in ways to make vegan food more about community building than dividing, furthering the book’s message.

Bryant Terry’s Afro-Vegan is one of the few vegan cookbooks I own that both explores a cuisine deeply while elevating it to new heights. It’s one that I’ll grab when I need inspiration for something new and exciting, as well as the one I’ll dog ear and bring to Louisiana on family visits. Hopefully other chefs will be inspired as well, and we can further the cause of integrating veganism into our communities and family histories.